All of us here on the Farallones wish the best holiday cheer to the many folks who have supported us during the past year. The rich marine life here in the Gulf of the Farallones has attracted a human community that appreciates the Farallon Islands and the wealth of natural resources that exists here, and many help us with our research on this lonely rock perched at the edge of the continental shelf.

All of us here on the Farallones wish the best holiday cheer to the many folks who have supported us during the past year. The rich marine life here in the Gulf of the Farallones has attracted a human community that appreciates the Farallon Islands and the wealth of natural resources that exists here, and many help us with our research on this lonely rock perched at the edge of the continental shelf.We made a great feast for the solstice with the groceries our Farallon Patrol coordinating angel, Brandy Johnson, arranged to be delivered on the 'Chelsea Lee' out of Sausalito. After big seas and high winds scrubbed our scheduled weekend Farallon Patrol run, skipper Harry Andrews and his crew Brett and Chris graciously rearranged their schedules, making a weekday dash to the islands during the one day of decent weather in the week of the 17th. We depend on these volunteer skippers of the Farallon Patrol who use their own boats to keep the island biologists fed, and delivering parts so we can keep our self-sufficient power and water systems running. Thanks Brandy and Farallon Patrol skippers and crew.

We received an early present the week before, when Brandy and Albertha arranged for Jared on the crab boat 'Bright Future' to deliver a cell phone to the island during a period when our radio communications were down and we were cut off from the mainland. Thanks Brandy, Albertha and Jared.

Many of the working boats of the charter boat fleet support our research on the Farallones by transporting critical equipment or personnel to/from the islands during their fishing/crabbing/shark- and whale-watching trips. Special holiday greetings to Mick and company on 'Superfish,' as well as the folks on 'Butchie B.,' 'California Dawn,' ' Wacky Jacky,' and the boats of the Oceanic Society and SF Bay Whalewatching. Thanks to everyone in the charter fleet. Thanks also to and Ron on 'GW' for checking our buoys.

Many of the working boats of the charter boat fleet support our research on the Farallones by transporting critical equipment or personnel to/from the islands during their fishing/crabbing/shark- and whale-watching trips. Special holiday greetings to Mick and company on 'Superfish,' as well as the folks on 'Butchie B.,' 'California Dawn,' ' Wacky Jacky,' and the boats of the Oceanic Society and SF Bay Whalewatching. Thanks to everyone in the charter fleet. Thanks also to and Ron on 'GW' for checking our buoys. A big year-end thanks also goes out to Rick, Steve, Ernie and the rest of North Coast Divers for being the most enthusiastic crane installers and maintainers we've ever had the pleasure of having on the island. You guys obviously appreciate the Farallones, and that makes all the difference.

A big year-end thanks also goes out to Rick, Steve, Ernie and the rest of North Coast Divers for being the most enthusiastic crane installers and maintainers we've ever had the pleasure of having on the island. You guys obviously appreciate the Farallones, and that makes all the difference.We on the island are especially grateful this winter for the kind gifts from two special Santas, Joan Lee and Margaret Lewis.

Francine at Clairol also sent us our annual gift of product to mark the elephant seals with. Thanks Francine and Mary.

Of course, we must also thank Joelle and Jesse at the Refuge, and the Sanctuary folks as well for all that they have done this past year to make our research on the Farallones a success.

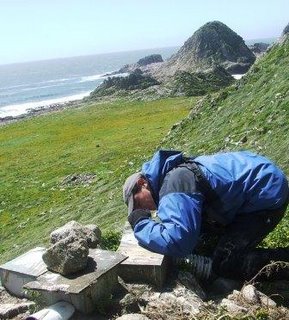

Black Storm-petrels are the largest of the storm-petrel species commonly seen along the west coast of North America, and are considerably larger than both Ashy and Leach's, as can be seen in the photo below. The bird on the left is an Ashy while the bird on the right is the Black. It also has a much stockier build, longer wings, larger bill, and stronger bite than the Ashy (as the person in this photo discovered just prior to releasing the bird).

Black Storm-petrels are the largest of the storm-petrel species commonly seen along the west coast of North America, and are considerably larger than both Ashy and Leach's, as can be seen in the photo below. The bird on the left is an Ashy while the bird on the right is the Black. It also has a much stockier build, longer wings, larger bill, and stronger bite than the Ashy (as the person in this photo discovered just prior to releasing the bird).