Storm-petrels are diminutive little seabirds usually only glimpsed for a moment as they flutter

over the surface of the ocean. They are part of an order of birds know as Procellarids, more commonly called the "tubenoses" for the presence of a specialized structure that encases the nasal openings on the top of the bill. They are long lived, with records of individuals in excess of 35 years old, lay a single egg each season which they will rear over the course of several months, and are the most pelagic of all seabirds which breed on the Farallones. Storm-petrels travel great distances from their breeding colonies in search of food, sometimes up to 250 km in a single foraging trip, and spend most of their lives in the open ocean. They are primarily nocturnal at the colony, returning only after full dark in order to take their turn incubating the egg or to feed waiting chicks. Approximately half of the world's population of Ashy Storm-petrel breeds at the Farallones along with a small population of Leach's Storm-petrel.

over the surface of the ocean. They are part of an order of birds know as Procellarids, more commonly called the "tubenoses" for the presence of a specialized structure that encases the nasal openings on the top of the bill. They are long lived, with records of individuals in excess of 35 years old, lay a single egg each season which they will rear over the course of several months, and are the most pelagic of all seabirds which breed on the Farallones. Storm-petrels travel great distances from their breeding colonies in search of food, sometimes up to 250 km in a single foraging trip, and spend most of their lives in the open ocean. They are primarily nocturnal at the colony, returning only after full dark in order to take their turn incubating the egg or to feed waiting chicks. Approximately half of the world's population of Ashy Storm-petrel breeds at the Farallones along with a small population of Leach's Storm-petrel.Twice a month, we go out in the middle of the night to mist net these incredible birds as they return to the colony. This work is part of a long-term mark/recapture study to assess population status and trends and to estimate survival. But on April 22, we had an unexpected visitor to our colony, the Black Storm-petrel.

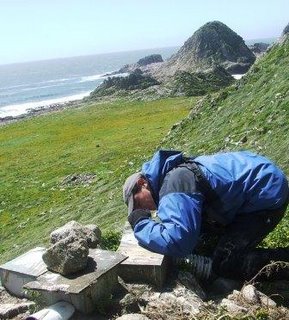

Black Storm-petrels are the largest of the storm-petrel species commonly seen along the west coast of North America, and are considerably larger than both Ashy and Leach's, as can be seen in the photo below. The bird on the left is an Ashy while the bird on the right is the Black. It also has a much stockier build, longer wings, larger bill, and stronger bite than the Ashy (as the person in this photo discovered just prior to releasing the bird).

Black Storm-petrels are the largest of the storm-petrel species commonly seen along the west coast of North America, and are considerably larger than both Ashy and Leach's, as can be seen in the photo below. The bird on the left is an Ashy while the bird on the right is the Black. It also has a much stockier build, longer wings, larger bill, and stronger bite than the Ashy (as the person in this photo discovered just prior to releasing the bird).  Black Storm-petrels breed on offshore islands from Baja California, Mexico north to the Channel Islands and in the Gulf of California, but the majority of the world's population breeds on San Benito Island in southern Mexico. They are typically seen off the coast of southern California, but may also be seen in Monterey Bay and the Gulf of the Farallones during the winter. However, it is rare for this species to be observed this far north during the breeding season and is the first spring record for the Farallones as well as the only one ever caught on the island. The occurrence of this Black Storm-petrel on the Farallones, in addition to being exciting for those of us living here, illustrates the impressive foraging range of these birds and the unpredictable nature of life on this island.

Black Storm-petrels breed on offshore islands from Baja California, Mexico north to the Channel Islands and in the Gulf of California, but the majority of the world's population breeds on San Benito Island in southern Mexico. They are typically seen off the coast of southern California, but may also be seen in Monterey Bay and the Gulf of the Farallones during the winter. However, it is rare for this species to be observed this far north during the breeding season and is the first spring record for the Farallones as well as the only one ever caught on the island. The occurrence of this Black Storm-petrel on the Farallones, in addition to being exciting for those of us living here, illustrates the impressive foraging range of these birds and the unpredictable nature of life on this island.