Me banding some Brandt's cormorant chicks in "Business Causal" attire - Farallon style

Thinking about the passage of time out here has me pondering some of the big changes I've observed in island wildlife and our lives out here since my first seabird season as an intern back in (yikes!) 1998. I distinctly remember going over to the Coast Guard house that summer to watch the latest episode of X files and the final episode of Seinfeld on the old TV with rabbit ears. The Unusual Events section of the journal the day I first arrived (April 11th, 1998) reads “Set up a new entertainment center courtesy of Russ Bradley – we are now caught up with the times and can listen to CD’s!”

Who didn't rock the Discman in the late 90's?

Here are some of the big changes I've seen over 17 years at the Farallones

Fur Seal Recovery

I don’t think we saw any fur seals back in the summer of 1998, as they had only started pupping on West End in 1996 after over a century and a half of extirpation. When I became a Farallon Biologist in 2002, seeing a couple Fur Seals on Indian Head beach during late summer pinniped surveys from the lighthouse was a treat. And the few animals that did breed were out of our view. I never would have imagined they would have increased so rapidly, with over 1000 individuals including over 600 pups in the West End colony. Indian Head beach is now full of breeding fur seals in the summer, and last October I was utterly amazed to be sitting above Indian Head Beach on a West End Survey with wall to wall fur seals all around, and several hundred in rafts floating just offshore. As this population continues in its recovery and more fur seals begin to reclaim Southeast Farallon Island, there may be even more drastic change to come.

Fur Seal pups on West End

Return of the Murres

When biologist Kelly Hastings first took me up to the Shubrick Point Murre Blind, I was blown away by how many Common Murres were there on the breeding colony and especially across to the northwest on Fertilizer Flat. Now 17 years later, that population has increased in size by over 5 times, and if you include birds from the North Farallones, there are well in excess of 300,000 Common Murres breeding here on the islands. That is the most since the egging days of the mid 1800’s. The rapid population growth in the early 2000’s during several years of productive ocean conditions was exemplified by the moment when fellow Pete Warzybok and I were counting murres below the lighthouse on the massive Fertilizer Flat colony. We realized that there were just too many to count accurately by conventional means. Even though we were both very experienced murre counters, we were getting lost in “the blob”, a contiguous mass of over 15,000 birds all touching each other with few prominent landmarks. Thanks to our continued work counting monitoring plots, and aerial survey work from our partners at the USFWS – we can continue to track this amazing resurgence.

Murres with their egg at Sea Lion Cove

When I came to the Farallones, we were entering data into a computer with Dbase III (for all you kids out there, you couldn't copy and paste in Dbase III), had one shared text based email account on an ancient laptop we were afraid to turn off for fear it wouldn't turn back on, and communicated with the outside world primarily through one way radiophone. In 1998 I remember one of the interns coming back from her break with a new camera and for 2 weeks she shot a roll of slide film per day. That’s 36 pictures in a single day! How could you ever take and develop that many pictures…. When we got our first digital cameras in the early 2000’s, which held 3.5 inch floppy disks, they could take 5 pictures. A far cry now from all the incredible digital photography the island has produced in recent years: like this shot, one of my favorites from the incredibly talented Annie Schmidt...

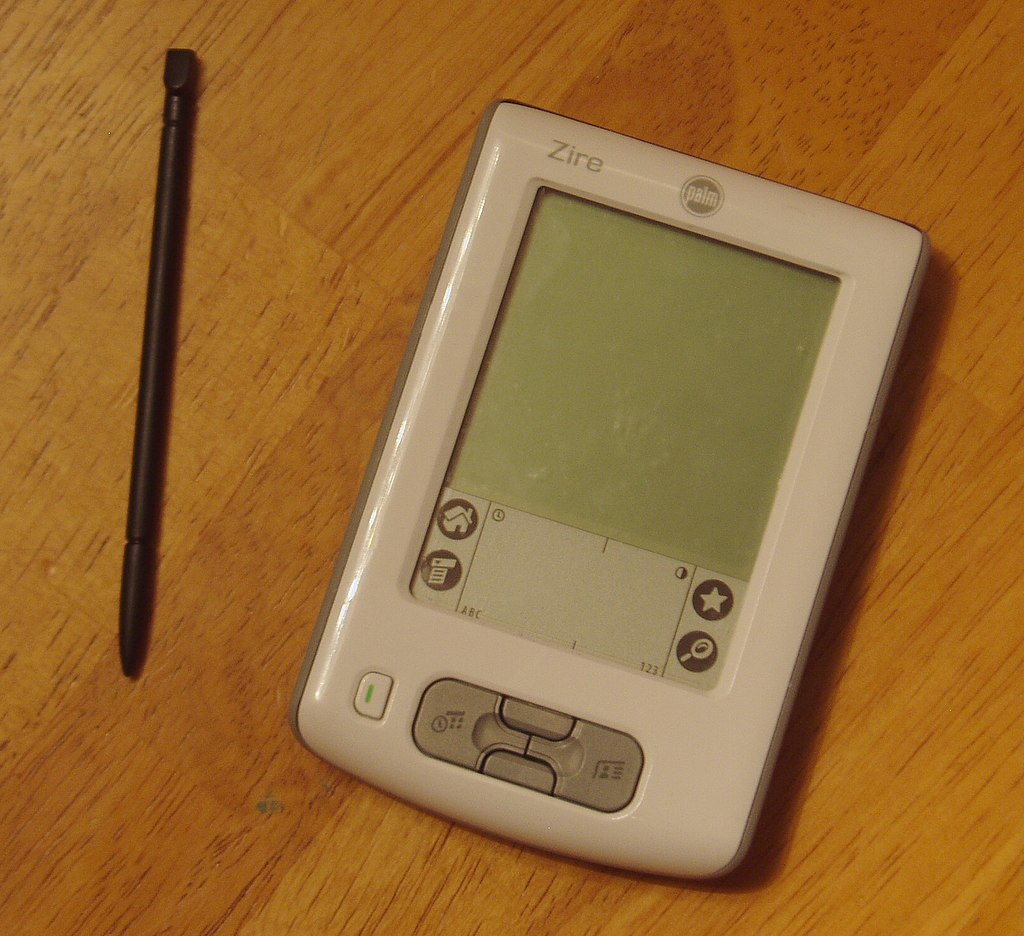

Analog cell phones used to work well from the southeast corner of the island, and many of us used them in the early 2000’s to avoid the quirks of the radiophone. I remember once talking to my cell phone provider from East Landing about my bill and the agent asking about the persistent squawking in the background “Is that a Chihuahua making all that noise?” I replied “No, it’s a just a couple thousand Western Gulls”. About 2011 we were still using Palm Pilots (remember those?) to collect data digitally for seabird diet studies. We realized from the blank looks on the faces of our interns as Pete and I regaled them about our use of this great new technology that we were already behind the times again… Needless to say technology advancements have greatly benefited island data collection, communications, and even research with new wildlife tracking studies. But with all these advancements we try not to lose the simple pleasures of being with enthusiastic and amazing people in such a special and remote place.

The Palm Zire, ground breaking data collection technology....

just not so much in 2011 when we were still using it

New Ecosystem Studies

In the early 2000’s I used to bemoan the fact that most of the journal entries relating to our endemic Farallon Salamander consisted of such scientific nuggets as “Saw one under a rock.” Well I’ve been very happy to see our new comprehensive research on island salamanders, insects, and plants really take hold in recent years – along with help from partners at USFWS and local universities. This new work has helped us to understand more of the unique Farallon ecosystem. Do you know that Farallon salamanders are extremely territorial and will often stay within about a half meter area once they emerge after the first rains? Or that the majority of the world’s population of the endemic Farallon Camel cricket lives in one huge cave on Shubrick point near massive murre colonies?

Measuring a Farallon salamander

Infrastructure Improvements

We wouldn't be able to run the program we do on the Farallones without the help and support of our biggest partners, the US Fish and Wildlife Service. One of the Service’s great contributions is their involvement in maintenance of island facilities. When I first game to the island, our “gray water system” was a garden hose that ran from the washing machine into rusty metal garbage. You would then take a 5 gallon bucket from that to use the bathroom facilities – and our “septic system” was a terracotta pipe that ran to the ocean. Now with an efficient zero emission custom septic setup – along with our water collection, solar system, and reliable outboard engines (no more surprise rowing workouts during a landing) the island facilities run as smoothly as one could realistically expect, and we are indebted to our USFWS partners for all their help on this front.

Fixing the East Landing Crane

This “Old Man Farallon” counts himself as one of the truly lucky ones